I.

The only item purchased that day was a first-edition copy of Wallace Stevens’s Harmonium—the poet’s first collection, published in 1923. Its price was four thousand dollars. The buyer, an attorney in a yellow bowtie, handed his credit card to the store’s owner. “In lieu of a briefcase full of cash,” he said. Soon the owner, certain he’d have no more customers, shut off the lights and locked shut the doors.

II.

In his twenties, in letters to his wife, Wallace Stevens remarked that,“I mean to keep as busy as I can, so that in the end I shall have something to show for the trouble of keeping alive”;“I should like to make a music of my own, a literature of my own, and I should like to live my own life”;“I believe that with a bucket of sand and a wishing lamp I could create a world in half a second that would make this one look like a hunk of mud.” My father—an often-bowtied attorney, a collector with a credit card—owns a first-edition copy of the book in which these letters appear. He said to me once that if he’d had more courage he would have become a poet, not a lawyer.

III.

My father’s intention is to amass “one of the two or three most comprehensive privately held collections of Wallace Stevens’s stuff.” Toward this end he’s spent about $25,000 and is unsure why. “Investment isn’t really the game,” he tells me. “I’m not going to, like, sell this stuff down the line for six times what I paid. There’s something else going on.” In his living room two shelves are stuffed tight with Stevens paraphernalia: first editions of all Stevens’s books; several of the literary journals—Poetry, The Partisan Review, The Kenyon Review.—in which Stevens’s poems and essays first appeared; a copy—Stevens’s personal copy—of the acceptance speech he gave when receiving the National Book Award in 1955. (“One of the most gracious, most profoundly modest acceptance speeches I’ve ever read,” my father said. “My favorite part is you can feel the paper was folded into thirds. Do you feel that? You can just imagine it kept inside a coat pocket, or sealed in an envelope.”) What he’s missing is a first-edition of Harmonium, in its first binding, with an original dust jacket. The circulating copies run about $10,000, and although he is wealthy, my father believes this is too much to pay.

IV.

Wallace Stevens’s daughter, Holly, said of her father that he was usually a good speller, but regularly misplaced or omitted his apostrophes when using contractions and possessives. His handwriting, she remarked, was difficult to decipher. When she dropped out of Vassar during her sophomore year—it was 1942, and she “had felt no purpose after Pearl Harbor”—Stevens was greatly disappointed in her, though he failed to convince her to return. Also he disliked her first husband, and made it known. Holly, after her father’s death, devoted herself to his work, editing and releasing several volumes of his verse, letters, essays, and journal entries, correcting his apostrophes and, less often, his spelling. She died in 1992.

V.

When, during my childhood, my father collected chessboards, it may have been (this is my speculation) one of his many subconscious ploys to distract himself from admitting his true sexual desires to himself. When he collected cookie jars, I believed it was an expression of his longing to return to my mother, even though he never could; his cookie jar collection’s centerpiece—a porcelain owl, wearing spectacles—was one we’d had in my childhood home.

VI.

It’s strange to hear that one’s father is not what he wanted to be. To a child (to this son, at least), a father is what he is, and there is little room for other possibilities. And yet, my father has been two people in my lifetime: who he wasn’t and now, finally, who he is. Maybe one day he will write verse.

VII.

The critic Helen Vendler says of Wallace Stevens, “His manner was slow in evolving, and it evolved through his sense of himself and through a search for his own style.” She says, “If we find, in reading Stevens, that he tries and discards mode after mode, genre after genre, form after form, voice after voice . . . we also find a marvelous sureness mysteriously shaping his experiments.” She says, “His wholes were always melting into each other . . . his work was all one poem to him, clearly, but yet he did divide it into parts.” These observations, loosely yet easily, transfer into my thoughts of my father.

VIII.

In college I spent a lot of time with poetry, and I gravitated toward Stevens for lots of reasons. He’s a little bit arch, a little bit urbane. And let’s face it—I’m a little bit arch. That’s me. And you know he was a lawyer, so there’s that. And what he does with language. He’s sound, voice: poetry. There’s a post-transcendentalism that he has and to me that’s a truth. I think he’s figured out—and gotten right—how our imagination is what makes us human, and is also an extension of the natural world.”

IX.

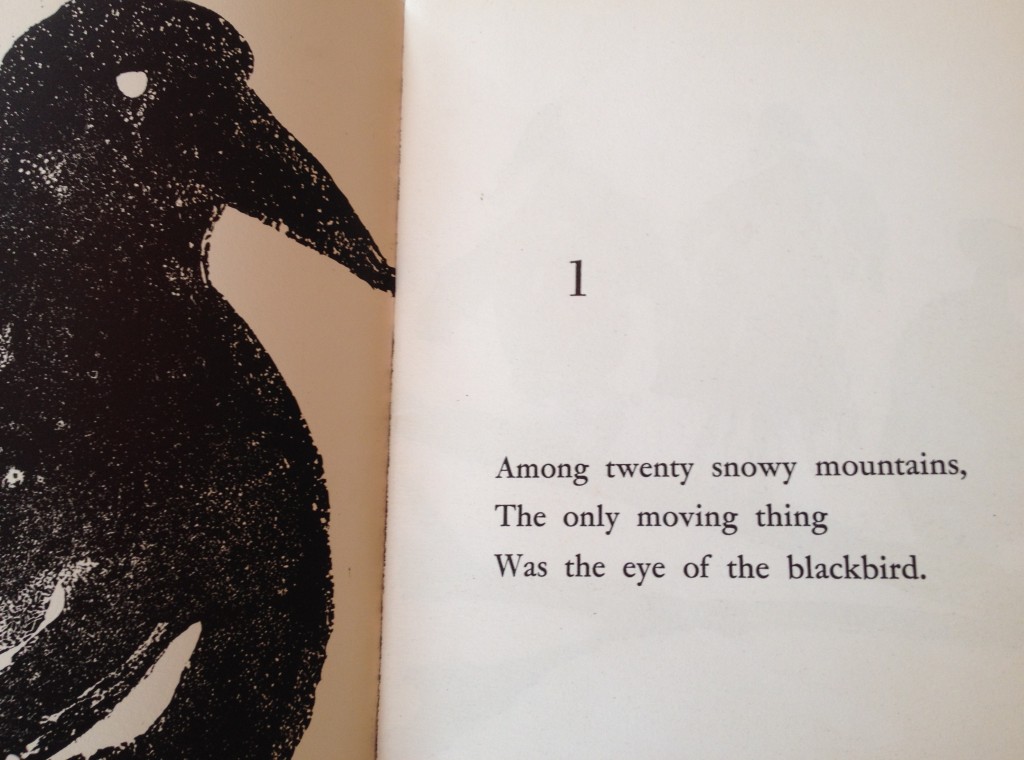

My father held up a second-edition of Harmonium. “It probably ran me a hundred bucks. Back then a hundred bucks was a big deal. Just look at it: the pages are yellowing a little. It has that smell.” We were in his living room during halftime of NCAA quarterfinal game between Louisville and Duke. One of Louisville’s sophomore guards had just broken his leg after trying to block a shot; his shin had developed an unnatural hinge; the station replayed the accident over and over and my father and I decided to turn off the TV and look at his Stevens collection. Between us, on a side table, was a glass replica of the Chrysler building, filled as always with Ghirardelli chocolates. My father held up another book, The Man with the Blue Guitar. “I was in Dinkytown. This must have been the late eighties. I saw this for eighty-five dollars. I thought why not?” And another: “This is from Will Ransom’s library—he’s a well-known collector. You see it still has his seal?” The sun hit the glass pendants of his hanging chandelier, and slivers of light, as if from a disco ball, sprayed onto his books. “I got this one for seven hundred dollars in the mid-nineties, in New York, at a place called House of Books, which is long out of business. It’s worth about ten times what I paid for it.”

“Yes, this guy here is rare.”

“I was with your mother. It was Rosh Hashanah, funny enough. We were in the store and I saw it. That was the beginning of my book collecting.”

X.

In editing and selecting her father’s correspondence, Holly Stevens devoted “two years to this work without interruption.” There were more than 3,000 letters to sort through, spanning sixty years. To a colleague he wrote, “I have been thinking it might be possible to . . . find some girl of intelligence and tact who would make friends with Holly without her knowing why and . . . help us carry her over whatever the difficulty may be . . . I want her to go through college without interruption. She isn’t a brilliant scholar and I don’t make a point of that; I do make a point of the regularity and discipline of the thing. She is an only child, and this tends to introduce a certain amount of disorder in her . . . I should be willing to pay anyone whose assistance you thought might be of help.” In her introduction to the Letters, Holly Stevens wrote, “It has been a privilege and a pleasure to work with this material and to present, through this selection, Wallace Stevens as an ‘all-round man.’”

XI.

The instructor told us to sit; we sat.

Thirty rears pressed softly down

On thirty yoga mats.

My father grunted through his nose.

A limber dandy, Daddy: he can touch

His toes (with his elbows).

I can’t. Throughout the class the instructor—a friend of my father’s (part of the social circle he found soon after he came out)—rearranged my arms and legs. His hands were soft and lingering. He remarked how much I sweat. “You didn’t know yoga was so difficult, did you?” he whispered. It is difficult to feign nonchalance with sweat running down one’s face, as one’s thighs quiver with effort.

After he’d curled into the fetal position (a strange thing for a son,

This son at least, to see), my father turned to lie on his back.

Things as they are, I thought, are changed upon the yoga mat.

XII.

For twenty years James and Mary Laurie Booksellers was situated on Nicollet Mall, in downtown Minneapolis, next to a tequila bar. Its website claimed a stock of more than 120,000 books, as well as 30,000 vinyl records, and a sizable collection of rare old maps and prints. The front of the store, where the windows were, brightened toward midday, but if one went deeper in—toward the fiction section’s X‘s, Y‘s, and Z‘s—things got dark. Out of this darkness, on one of the store’s last days of business, its owner, James Laurie, appeared. There was a tinge of surprise that someone had entered his store. He had short white hair and a short white beard and moved with the stuttering gait of a retired basketball player. Over the years he tracked down all the books in my father’s Stevens collection. I introduced myself as my father’s son. “We have to be out of here by July first,” he said. “Another restaurant is moving in.” I asked if he knew where he would move; he said he didn’t have a clue.

XIII.

To collect: to seek out, own and arrange, to fit together disparate members of a genus, to imbue an object with a personal value that surpasses any of its other values. “There have been large changes in how I view acquiring,” my father said. “There used to be this whole fetish element to it. Even now the whole process isn’t rational; I can’t tell you what the rationale is. It’s fun—whether it’s cookie jars or whatever, it’s all about the hunt. But I don’t know the end game. The worst thing that could happen would be that this collection ends up in a dark corner in some rare books store. I’m trying to pull these things out of those bookstores. If I had my vote, what I’d like is for these to end up with you, as the cornerstone to something.” He stood from his chair and began folding shut all the books to put them back on his shelf.