This cat Fritzel was odd. She wasn’t pretty like Angel or Bon Bon, and she wasn’t smart either. Just one of those weird, piebald cats with personality issues. Maybe I didn’t like this cat so much. But once you have a cat, you keep it until it dies. When Fritzel was a kitten, she charged face-first into my dad’s knobby middle knuckle and half-blinded herself, turning one eye opalescent. That didn’t help her looks.

Fritzel often napped in a spiral beneath my mom’s painting chair. Late one afternoon, turpentine sloshed out of its jar onto her back, and she licked herself dry. She did the strangest of death dances, cruised sideways and backwards all around the house with her tail stick-straight, frothing at the mouth and gurgling and grunting. Which was the end of Fritzel. So I know what turpentine can do, though I’m still guessing about its flavor.

Turpentine smells like Coca-Cola stripped of sweetness, with a dash of fiery death, and it’s the pervasive scent of my youth. In all the dozen homes we’ve inhabited (San Francisco, Mexico, in the Willits Valley, in the boondock backwoods of Mendocino County, in the house with an attic and ghosts and a horse, in the one-room apartment during the divorce) there’s always been this space: the art room.

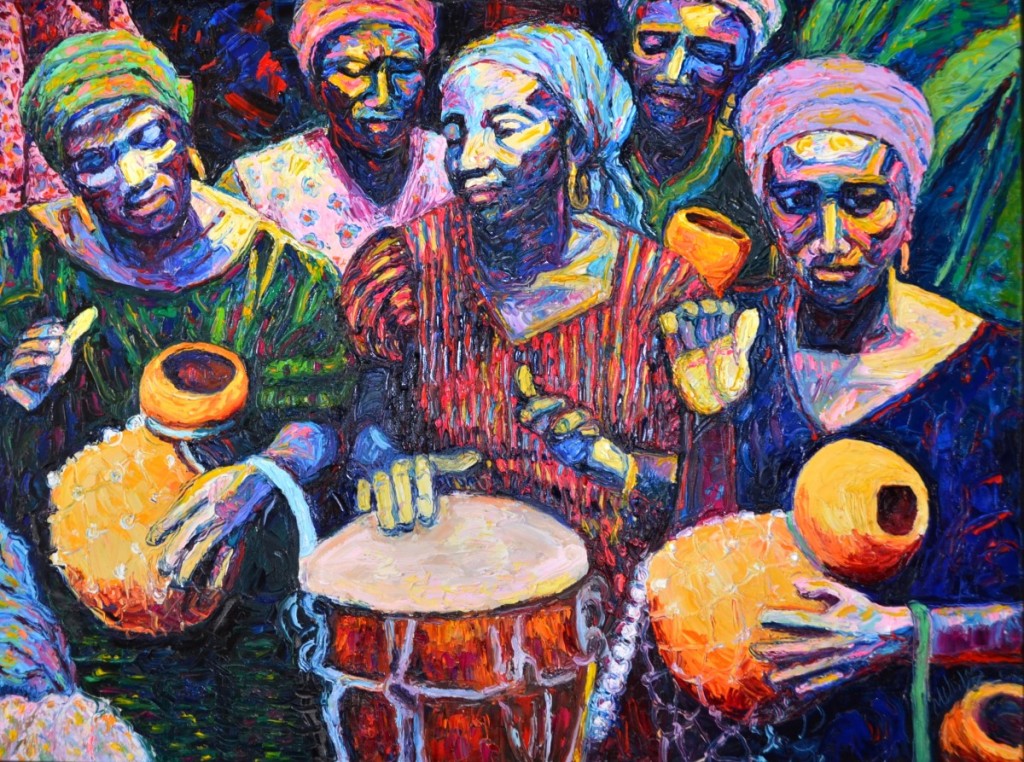

She’s listening to some schmaltzy soul, turned up loud—Anita Baker or Ashford and Simpson—really blasting it, like she always does when she’s in the zone. She can’t hear me breathe or peel splinters from the doorjamb. She doesn’t know I’m watching. A soggy joint hangs from the corner of her mouth. How long has it been there? Years? My mom is forever this way: legs splayed, wearing some stinky old shirt, fat ballooning over the seat of the chair, in deep meditation: consumed, entranced, enslaved, in love. God rides the edge of her pallet knife, dressed like a gob of fuchsia oil paint, which she’s about to smear into a combination of colors that is already over the top. Nothing—but nobody—interrupts when she’s in her painting chair.

It’s a straight-backed wooden chair, thumb-swiped in a trillion-zillion hues, from Interference Oxide Green to Napthol Red Light, Quinacridone Pink to Laudanum Yellow. She rocks back and squints, tilts her head this way and that, absently wipes her jungle-bird fingers on her shirt. The paint must be an inch thick. She reloads her knife and dives back in.

When the muse is gorged and satisfied, it will abandon her body like a used rubber glove, leaving her saggy and deflated, a formless, useless biohazard. My mom leans back in the chair once more and grunts. A loose ringlet slips across her forehead. She opens the tin of turpentine and the scent is a force.

Turp—we call it affectionately—stinks like lemons left rotting on the windowsill, stinks like the braided studio rug I secretly peed under when I was very small, smells like my mom’s chubby fingers, those magical instruments. If she dies before I do, I’ll place an open jar of it next to the sleeping side of my bed for comfort, and if I light a joint and drop the match in the jar, so what?

She dowses her rag and screws it around her fingers. She is smiling at the painting, but she’ll see me here soon. She’ll notice that I’ve been watching and smile for me. The turp rag flops onto the floor. She scoops a blob of indigo onto her pointer finger and scrawls her name in the lower-right corner of the canvas.